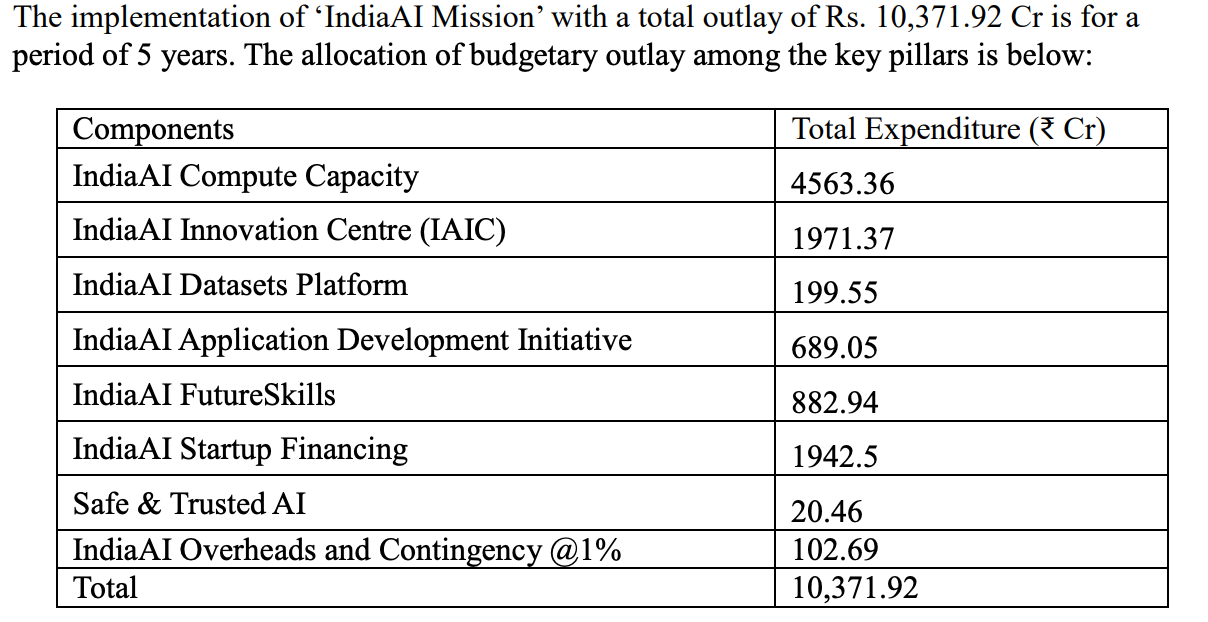

The Indian government recently allocated $1.25B to do something with AI over the next 5 years. Details are a bit murky to me, as are the overall goals. You can search for “India AI Mission” to find out more about it. Here’s a Perplexity summary: https://www.perplexity.ai/search/tell-me-about-the-india-ai-mis-0aVZDkmcRYSRIvPY7Au07g

Last Wednesday I walked into a room of lawyers, policy makers, educationists, industry professionals talking about this program, the AI ecosystem in India and the government’s role. It was about as eclectic an audience you could find; the discussion was tightly moderated, information-dense, impassioned, and covered more ground than I thought possible in an afternoon.

It was a privilege to participate; huge thanks to my friend Nikhil Pahwa for inviting me, and his team at Medianama for organizing it. I came away much smarter about the zeitgeist here, especially as a once-insider-now-outsider.

These are my reactions to the discussion; I’ll try to highlight some interesting tension points that I observed.

1. Frugality

Yes, the budget for this India AI Mission is small. $1.2B over the next 5 years is tiny compared to how much AI startups in San Francisco are raising. But then, India’s recent Moon landing (4th country to ever land on the moon, 1st on the moon’s south pole) was also accomplished successfully with a budget of only $75M (yes, M not B). Contrast that with China’s 2019 moon landing for $120M or Russia’s 2023 crash landing for $200M or Nasa’s multi-billion dollar programs like the recent Artemis I (although that was greater in scope).

A small budget isn’t surprising. Frugality is part of the ethos and has served the country well. What it does result in downstream are efforts like making LLM training efficient on CPUs to save on GPU cost. Admirable? Yes. The highest leverage effort? Unclear.

One one hand, it is inspiring to see the frugality and see it work: we’ve been able to “do rocket science” rather cheaply. On the other hand, Silicon Valley (and the FAANG culture) teaches you to always be asking: what would you do if you had infinite resources. There is some value in the pig-headedness that comes from abjectly refusing to accept resource constraints.

2. Mistrust of the West

Whenever the Sarah Paine lectures hosted by Dwarkesh make it to Youtube, the 3rd part is an excellent overview of how the US - India relations went during the cold war and actions of the US during the various India <> Pakistan / China wars to alienate India (that have not been forgotten).

One of the questions posed to the room (by yours truly) was whether India having its own foundational models had national security implications. Little did I realize it would turn out to be the most heated topic of the day. “Of course we need our own models, we cannot depend on western institutions” or “Let’s just use the open source models and host them ourselves, why train from scratch” or “Western models will not suit our objectives” or “We can’t give them our data” being the vehement exhortations. A few people brought up how the US sanctions in Russia have impaired Russian payment rails; one person even said that the US is the only country that once sent aircraft carriers to India as a threat — I don’t think that’s true, but it goes to show how mistrust of the west hangs in the air along with the humidity here.

Someone brought up how Brazil forced Meta to stop using Brazilian user data to train their models, and scrub their models, and how India (with its leverage of being Meta’s largest user base) could also do something similar. It was fascinating to see how quick everyone is to empower the government (”us”) against western institutions (”them”). Contrast that with debates in the US about the TikTok ban and its implications on free speech.

That said, India opened up its economy in the early 90s and saw tremendous growth as a result of it, and that has not been forgotten. People want an open economy and are unafraid of competition.

3. Trust in the government

It is impossible to wear rose-colored glasses about the government in India. The difficulty of working with government organizations, getting them to share data, the ground reality of politicking was oft acknowledged in the room. “The government has never been transparent about anything, that’s not going to change now” is a verbatim statement from one of the participants pointing out challenges with India AI Mission. Flaws of the MEITY and the vagaries of its Data Protection Act came up.

What (pleasantly) surprised me was that in spite of this, there is a willingness to work with and through the administration. At some level it is considered the right thing to do. Many people in the room were already working with different levels of government to offer them AI services, make government data more useful. These initiatives seemed grassroots, to the credit of the individuals trying to run through the proverbial wall. There is desire to contribute to the government-driven AI programs and regulation.

Even though it isn’t clear if there is a northstar behind the government’s AI initiatives and details of how the $1.2B is going to be spent are murky, there is optimism about the India AI Mission and the government directly building foundational models.

That said, it was surprising to see the idea of regulating something as nascent as AI being embraced. No argument was made for not regulating at all. Regulation is at odds with innovation, especially on the frontiers of tech, and the discussed solution was regulatory sandboxes. The fact that these become political machinery was not a deterrent.

To me, pmarca’s famous metaphor of “government sushi” comes to mind, and I wish there the government directed itself at fostering an environment for businesses and academia or creating a healthy, competitive market rather than getting directly involved.

4. Tied down by nostalgia

Preserving the stories and mythology of remote communities, saving languages at risk of being forgotten, aggregating reactions to popular culture or current affairs from people who are not online — this is the data top of mind to aggregate and collect. Translating the internet and making it accessible to the Tower of Babel that is India was one of the most cited use cases of LLMs.

Ties to history, culture, nostalgia, tradition are deeply ingrained in everything, and often claimed as the unique selling point of even modern technology. It feels like a minor point, but is broadly emblematic. You have to wonder when the deep roots prevent a thing from taking flight.

Someone once told me that in America history is just a thing that happened once upon a time, but in India history is a core part of everyone’s identity.

5. Misallocation of talent

My main critique of what I heard that afternoon is the misallocation of talent. I heard laments about the lack of AI talent in the country, or the ‘brain drain’, but I think the larger issue is not pointing the existing talent in the right direction.

The examples above of spending cycles in figuring out how to train on CPUs to save money on GPUs, or the emphasis on cultural use cases of LLMs are indicative of this. Growth simply isn’t as high a priority as it should be.

Much of the focus of the current AI effort seemed to be within the well-understood universe of LLM and their applications, or in mitigating potential harm, not in forward-looking research. Outside of the desire to be self-reliant, there was pushback on why India might even need home grown AI technology. The downstream implications of simply being technologically advanced is not appreciated enough. The subliminal tension between not trusting western institutions and yet not being willing to take them on at their own game seemed very odd to me.

The potential of applying LLMs seemed limited to domestic use cases: where is the desire to create a global platform, or a trillion dollar company? A pet-peeve I have of the Indian tech ecosystem is the tendency to jump to “X for India” ideas, where X is an already successful idea proven elsewhere (often the US). It’s a local maxima. Aiming to solve for the world is more likely to lead to larger outcomes.

If you ask me, existence of talent is not the constraint, allocation of the existing talent is. The government has the luxury of taking riskier bets where the payback period may not be within line-of-sight, and should allocate money to more research-for-research’s-sake initiatives and fostering homegrown companies with more incentives and fewer regulatory hurdles rather than directly participating in the application layer.

6. This is fine

Know that meme with the dog in the middle of a burning room drinking his coffee, and saying “this is fine”?

India is an economy that has become primarily services based. Of that, a large proportion is various types of white collar jobs: all the way from the large governmental apparatus to the back-office for the world to everything else in between as domestic businesses have grown and become more corporate-like. India’s largest services export is of BPOs: ~300B annually. The odds that most of this work turns into a prompt for an LLM is very high. Yet, in all my conversations with people here (not just this one afternoon) no one seems to be worried, much less planning, for the economic and social disruption that is sure to hit like a tsunami.

If you’ve made it all the way here and are wondering what “jugaad” means, here you go: https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Jugaad

Awesome! Thanks for sharing your thoughts and summary