Shaping your organization culture early with Sapir-Whorf

The movie Arrival, linguistics theory and Dilbert come together in argument for paying close attention to the early tools and rituals of any new / growing organization

All calendaring products optimize for the producer (people scheduling meetings) over the consumer (the meeting attendees). A surfeit of features make it easier and easier to play ‘calendar Tetris’ and schedule meetings. On the other hand, calendars are a barren wasteland when it comes to helping you manage your time. Sure, go ahead and create a “Do not schedule” block and see how effective that is. Not to mention the social dynamics in play — once someone has thrown a meeting on your calendar, the ball is in your court. You can appear rude and decline, but if you’d rather not, you’ll find yourself wrangling calendars and taking on the co-ordination burden to reschedule. It turns easier to simply take that meeting, fragment your time and plan to work after dinner.

The tools we use shape our work culture.

The Sapir-Whorf hypothesis

The Sapir-Whorf hypothesis is a linguistic theory that language affects cognition and hence people’s perception of the world around them. One of my all time favorite movies (Arrival) punches you in the gut with it, so indulge me while I liberally quote from the movie here. ***SPOILER ALERT*** If you have not seen Arrival yet, go watch it and come back!

In the movie, aliens arrive on earth, in multiple locations. In the US, a team of linguists, scientists and the military are trying to establish contact. Much of the movie is around their attempts to learn the alien language to understand why they are here.

Ian (the physicist) and Louise (the linguist) talk about the Sapir-Whorf hypothesis:

[Ian Donnelly] If you immerse yourself into a foreign language, then you can actually rewire your brain.

[Louise Banks] Yeah, the Sapir-Whorf hypothesis. It's the theory that the language you speak determines how you think and...

[Ian Donnelly] Yeah, it affects how you see everything.

Louise explaining to the Colonel why the language they use to set the baseline of interaction with the aliens is important, in contrast with what another country is attempting:

[Louise Banks] God... are they...? They are using a game to communicate with the Heptapods?

[Colonel Weber] Maybe... why?

[Louise Banks] Let's say I taught them chess instead of English. Every conversation would be a game, every idea expressed through opposition. Victory... defeat. You see the problem? If all I ever gave you was a hammer...

[Colonel Weber] Everything's a nail.

They finally figure out why the aliens are here:

[Louise Banks] I know what it is.

[Ian Donnelly] What?

[Louise Banks] It's not a weapon. It's a gift. The weapon is their language. They gave it all to us.

[Ian Donnelly] So we can learn Heptapod?

[Louise Banks] If you learn it, really learn it, you get to perceive time the way they do. So you get to see what is about to happen. Time — it isn't the same for them. It is not linear.

Louise has been the one learning the alien language, and it changes how she thinks and perceives the world, particularly her perception of time. She is aware of her future and her past all at once. The story is very poignant because of her ability to do that, but I’ll leave you to watch the movie to experience the grand opus Denis Villeneuve has created.

The tools we use at work have a similar effect. What they prevent or enable, make easy or make difficult become the rails for how we work. For example:

The easier it is to schedule meetings, the more meeting-heavy the culture will become.

If data is hard to access, decisions are less likely to be informed by data: expect more more intuition-based, or worse, influence-based decisions.

If you cannot schedule emails or messages, there will be work happening over the weekend or at odd hours, important or not.

Values need implementing

Every modern tech company has a list of values or principles it sermonizes in an effort to shape culture. The best founders start thinking about culture the moment the team size gets to three. It is important to create a north star for how people will make decisions, make tradeoffs, collaborate, and a list of shared values is the first step.

The most common efforts to instill values in an organization are actually posters in the hallways and various forms of proselytizing and rewarding behavior. However, if you stop at that, all you’ve done is:

Without connecting the dots from values to actions to culture in a tangible, almost Rube Goldberg-esque way, it is impossible to build culture — the set of default behaviors that you’d like to see.

Mark Zuckerberg, on The Tim Ferris Show, spoke at length about how they “implement” their values at Facebook / Meta:

[Tim Ferris] And I’d love to know how or if you are incentivizing these behaviors. You have a team that is determining how to facilitate supporting these values throughout the organization so that they do have more saturation, so to speak.

[Mark Zuckerberg] Each of these is basically coupled with an operational effort. So we have a set of work that we do. It’s like Move Fast is the work. Actually, it’s something that I’m pretty engaged in where I will just routinely go and sit down with, largely, engineering leaders, but also folks across the company and ask them, “Okay, well, what is slowing you down?”

You know this is important when the CEO of a half-a-trillion dollar company is himself involved in the brass tacks of culture building. After a few more minutes of describing their implementation of the recent revision to their company values, he says:

[Mark Zuckerberg] So I think that that’s one way to operationalize these, but you’ve got to operationalize them if you want them to be real. Otherwise, they’re just words that you put on a website somewhere.

It’s not just about coming up with alliterative phrases that make for great sound bytes.

Cultural values are important and everyone has them, and great companies work hard to inculcate them. Selecting your tools carefully, having them being used as you intend helps connect the dots from values to culture. Tools give rise to team rituals and they create paths of least resistance for default behavior, regardless of what is written in your hallway posters. Actions > Words.

Creating the ‘language’ for work

Levels is one my favorite examples of companies meticulously and painstakingly bringing their culture into existence. Mario Gabriele wrote about them recently, and here are some snippets that highlight their approach:

How does Levels manage across countries and continents with close to zero meetings? A thoughtful, intentional culture helps. So do dozens of Notion documents and hundreds of Loom videos.

In one of our discussions, he noted that Levels was not the right company for someone that saw work as a surrogate social home. He cited Airbnb as a successful maximizer of the social approach. Many of his friends that had worked there talked about the strength of the relationships forged. Corcos noted that while these bonds were beneficial during tough times, they came at a cost: the ability to do deep work.

For the CEO, it's a matter of picking your poison: There are trade-offs; everything is trade-offs. The trade-off [in the Airbnb model] is you probably have a much more resilient team. On a remote team, you might not have that same level of resilience...but you do have tremendous agency over how you spend your time. You have unlimited deep work, as much as you want.

Levels is a vigilant guard against synchronous communication. So determined is it to ensure that its team uses asynchronous channels it has written multiple internal documents outlining the "Principles of Effective Communication. For this reason, Levels favors tools that are naturally asynchronous and guards against those that lead to rapid back-and-forth. The same document illustrates how the team divides up these tools and highlights a "danger zone”.

Corcos discusses how he found Slack a "slot machine." Its constant barrage of messages and intermittent reward schedule ("ooh, a funny meme!") give it an addictive, dopamine-harvesting quality.

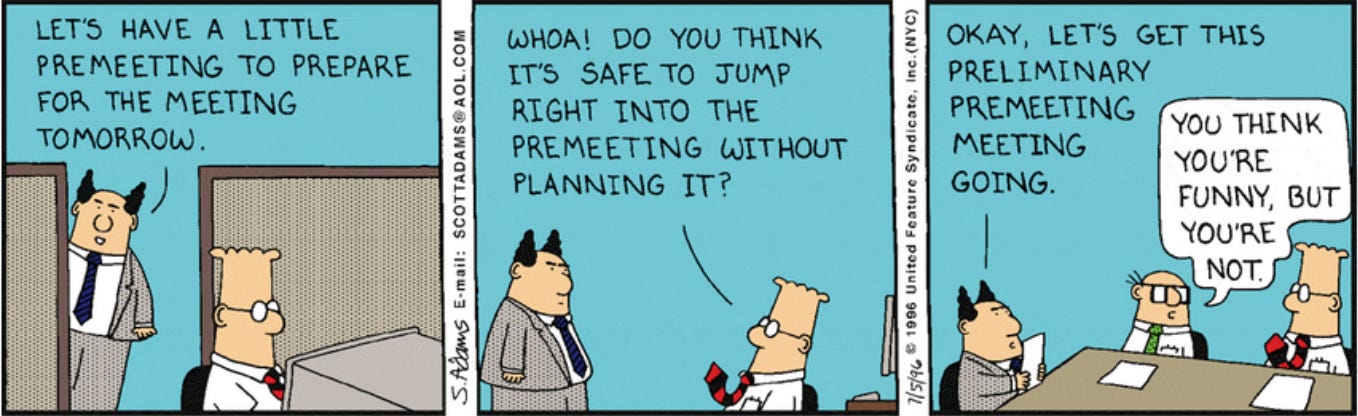

Many companies default to the usual set of productivity tools: Google Suite (email + calendar + docs) + Slack + Confluence + JIRA and let teams build their own processes or let them select their own tools in a survival-of-the-fittest hunger games, often inadvertently resulting in a culture like the one that inspired Dilbert.

“Btw, our Confluence is stale, look at this Google Doc for the latest roadmap”

“Setting a 30 min meeting but I don’t need more than 10 minutes. Do you have other things to discuss?”

“Quarterly OKRs are due, can you please ask your team to update their JIRA tickets, then enter the summary in this Google Sheet. I need to finalize Confluence by tomorrow.”

And the most common of all: “Should I create a Slack channel for this or an email list?” (the most common answer, terrifyingly, ends up being “both”).

The best companies, like Levels, take a different approach. They lean into the idiosyncrasies of the desired culture and select tools and processes that they know will act as rails for actions that will reinforce that culture. Staying on those rails is a lot smoother than getting off.

Let’s look at some of the idiosyncratic tactics different companies adopt to serve their grander cultural impetus:

1. On calendaring

→ Tobi Luttke, the CEO of Shopify, once had all recurring meetings deleted for everyone, and now they do it regularly. Turns out, people felt socially awkward in cancelling a recurring meeting, and this removes the burden from them (source).

We ran some analysis and we found out that half of all standing meetings were viewed as not valuable. It was an enormous amount of time being wasted. So we asked, “Why don't we just delete all meetings?” And so we did. It was pretty rough, but we now operate on a schedule.

→ Shopify also made it acceptable to walk out of any meeting not useful to someone:

→ This is a great example of a founder watching their meeting culture like a hawk and protecting time (but they may need tools to scale this protectiveness as they grow). It is also a reminder that the default response to a meeting invite from a colleague is yes.

→ Instituting “No Meetings days” is a common salve after the meeting culture snowballs beyond control, but I have not seen calendars support this as a feature. Are they not talking to their customers?! While an admin team will create an all-day “No meetings” event on everyone’s calendar to serve as a reminder, finding meetings still getting scheduled over that block is the rule not the exception.

→ Google Calendar has support for ending meetings 5 minutes early — but in a world where meetings tend to go on and on unless there is a hard constraint, isn’t better to start 5 minutes late to force the duration?

→ Another example is the trend of keeping your calendar public inside the organization (in fact, keeping it private these days is seen as an annoyance). An interesting behavior that has given rise to is a colleague coming by (or Slacking you): “Hey, I was stalking your calendar and noticed this meeting that might be relevant to me. Mind if I join?”. This a direct example of the tool enabling something that results in more transparency that causes better collaboration.

(Can you tell that calendars and the ensuing meeting culture is my pet peeve?)

2. On meetings

→ Amazon has famously shunned the slide deck in favor of 6-page long memos for staff meetings — read in silence at the beginning of the meeting as if in a study hall. This process is not the culmination of rigorous thinking but is upstream from it, not to mention that the meeting discussion is much more effective. (The anatomy of an Amazon 6-pager, The silent meeting manifesto)

→ Daniel Ek, CEO of Spotify, on meetings (source):

I think that's the single largest source of optimization for a company: the makeup of their meetings. To be clear, it's not about fewer meetings because meetings serve a purpose. Rather, it’s key to improve the meetings, themselves. A lot of my efforts focus on teaching people this framework. Ironically, I find that most people are just challenged by that stuff.

3. On internal communication

→ Stripe is famous for making all email public in their early days, leading to greater transparency and lesser politicking.

→ In a similar vein, Plaid did not allow the creation of private Slack channels. If you needed an exception, you could ask an admin to create one for you. This allowed flexibility while the path-of-least-resistance opinionatedly guided you towards greater transparency.

→ Some companies develop norms around weekend communication. While not enforced, tools that allow emails or Slack messages to be scheduled make it easier for this policy to be followed. The idea is that an individual should be able to work on the weekend if they like without having peer pressure cascade an artificial need to work weekends throughout the organization.

4. On data-driven decisions

Every exec says they’d like their teams to be data-driven, yet how many carve out the budget to make that easy for their teams?

→ At Zynga, everyone (yes, everyone) had access to a database of sampled data of ... well, everything, and SQL classes were part of the onboarding program. The idea was that anyone should be able to run basic queries to inform their decisions. The tradeoff made was that the database had to be small enough to let everyone to be run their (often suboptimal) queries and yet have enough directional signal to inform good decisions. The result was what you would expect.

→ Facebook has one of the best product experimentation frameworks that engineers can use to test how well their features perform. It makes it possible for anyone, even an intern, to form a hypothesis, build a feature to test it, and actually test it. When they famously had the entire company focussed on getting new users to 10 friends in 7 days, it was possible for anyone with an idea to quickly test it and see if it was actually good.

→ Scaling objective decision-making has benefits beyond the quality of the decision itself, in empowering people, reducing hierarchical bottlenecks and reducing politicking.

5. Other cultural stimuli

→ Not a tool per se, but Shopify allows employees to reimburse the game Factorio and encourages them to play it as it helps players build muscle in systems thinking.

→ Slack bots that randomly connect two people in the organization to have a coffee chat (often the coffee is reimbursable) build social fabric especially as organizations scale.

→ Using OKRs to drive product development has become controversial of late, as people realize the downsides of the process outside of large companies. It is easy for the process to become more important than the product and spiral out of control to the extent that there are now VC-funded SaaS tools to help teams manage OKRs: google for “okr tools”! As an example, this founder is decrying OKRs as a reason to join their company, and the replies to this tweet provide color on the current sentiment around OKRs:

These are specific examples to illustrate metaphorically the Sapir-Whorf hypothesis at work (pun intended) in the general productivity areas. Every function — engineering, sales, support, etc. — needs someone to wire its own culture similarly as you hire a function lead and start scaling it. Ultimately, what is needed is an entire system that reinforces the behavior and values you want to see in your company.

[Colonel Weber] Mornin'.

[Louise Banks] Colonel.

[Colonel Weber] (answering a previous question about the Sanskrit word for war and its meaning) Gravisti. He says it means an argument. What do you say it means?

[Louise Banks] A desire for more cows.

I like the Arrival reference 👍👍